Public inquiries and reviews

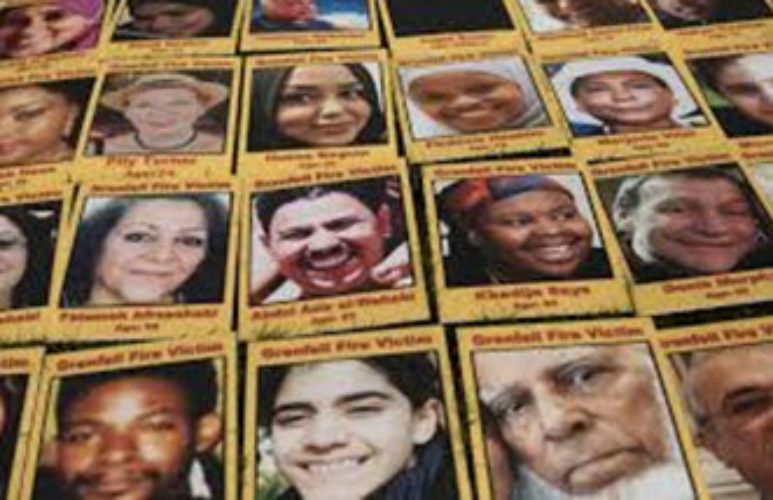

Today is highly significant. It marks the first day of the formal proceedings of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, following the initial ‘commemoration hearings’.

It’s encouraging to see that searching investigations at national level seem to be becoming more systemically aware. The Munro Review of Child Protection in 2010 marked a turning point in thinking this way (see our submission to the review). The current Food, Farming and Countryside Commission is clearly aware of systemic interactions between the different but related contexts. And investigations into both the Hillsborough and the Manchester Arena tragedies revealed systemic failures and generated clear messages about systems that held important implications for leaders and leadership processes.

And now we have the Grenfell Tower Inquiry chaired by Sir Martin Moore-Bick, and the associated Review into Building Regulations and Fire Safety chaired by Dame Judith Hackitt (whose report was published on 17th May).

Moore-Bick’s first question is ‘On the night of the disaser, how did the fire spread and what was the emergency response?’ But besides technical matters, he will also need to look into the nature of the relationship between the many players in the overall system before, during, and subsequent to the emergency: that is, the system that is responsible for designing, building, owing, letting, repairing, inspecting, regulating and running tower blocks and looking after the lives of residents, as well as fire-prevention, fire-fighting, advice and guidance and evacuation. How can that system’s interconnectedness be improved not only between professionals but also with the tower’s occupants?

‘Every single link in the chain is going to be found to be rotten and cancerous.’ Grenfell Tower resident.

We will briefly look at some of the systems ideas, issues and opportunities. And then we shall go on to see how some of the learning from this high-level field of inquiry can transfer and apply to investigating working life and jobs at a more individual managerial level.

Which system, and are we outside it or inside?

Using the metaphor of the fishtank to represent the organisation, it comes more naturally for managers and those in positions of authority to see themselves as a system outsider looking at what the fish are doing, who is failing, and then correcting them. (Download a free copy of How to see the system you’re in.)

Years ago, in British Airways, we had a daily operational meeting at Heathrow chaired by the general manager, a fearsome bully who frequently threatened managers with the sack. Each morning he wanted to find someone to blame for the previous day’s delayed departures. What he didn’t know was that all the departmental heads (catering, cabin crew, flight crew, servicing engineers, de-icing, etc.) always held a pre-meeting among themselves shortly beforehand in order to decide and rotate whose turn it would be to take the blame, so the pain would be equally shared out, regardless of the actual reason for delays.

The general manager positioned himself aloof and outside the fishtank. But the fish viewed him as a toxic shark, and they could manipulate him and protect themselves.

A more perceptive general manager might have been able to imagine being inside the tank, where things would look and feel somewhat different. The choice of perspective brings with it different responsibilities and a different focus of attention. Sometimes we are ‘a n other’ fish, and sometimes instead we are the owner, in charge of the food and oxygenation plus repairing leaks (forgive extending the metaphor). The nature and quality of managers’ connectedness is affected by the perspective: it determines who needs to change, and what can be achieved together.

What the general manager paid attention to and what he saw and concluded was shaped by what he wanted to find: namely, who could he blame for the previous day’s bad figures? He was not an impartial observer: observers never are. He was unconsciously introducing his personal bias. He was doubtless unaware of that risk and the price being paid.

Systems within systems

The result of the general manager’s lack of awareness was in not seeing there was a system within a system: i.e. the secret, pre-meeting operating between managers, and the formal accountability system that the GM thought was his domain and sole source of authority and learning.

In its own way and on a much larger and more complex scale, the Grenfell Tower Public Inquiry is also dealing with multiple systems within systems. Each of the professional parts has its own system of relationships, and there will be numerous unacknowledged shadow systems, if not on BA’s scale. There is also the insider/outsider role perspective.

Dame Judith Hackitt’s selective review was part of the wider inquiry into the tragedy. One part of her focus on the building regulations and fire safety aspects has been to review current practice at work in the daily operational system and to establish dysfunctional working. In this system she is an outsider.

In her second system, she is charged with designing and leading an improvement-recommendation process that is intended to make tomorrow work better than today. This system has some differences in membership, raising new relational issues. And here she has been inside the fishtank, both challenging and being challenged and lobbied by vested interests. A typical question for her to investigate would be ‘how could the installed fire safety doors have only half the fire resistance specified in the design? And what action should be taken?’ Is the explanation and response technical, economic, political or social – or all of these?

On 17th May, the day Dame Hackitt’s final report was published, the Rt Hon James Brokenshire (Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government) spoke to the House, endorsing her call for greater clarity and accountability over who is responsible for building safety during the construction, refurbishment and ongoing management of high-rise homes. Her review had showed that in too many cases, people who should be accountable for fire safety had failed in their duties.

There is a further system that needs looking into: the government’s and authorities’ implementation of recommendations from inquiries and inquests. How does the handover work? According to a Grenfell resident ‘The government didn’t implement the inquest recommendations after the Lakanal House fire where six people died in 2009. Had they done that, Grenfell wouldn’t have happened.’

To assist her review, Dame Hackitt produced a highly detailed systems map, clarifying the contribution played by the many parts, yet daunting in the range of interconnectivity. On the surface the map is essentially technical, but less obviously it implicitly reflects political, economic and social factors and historical and traditional elements and influences.

Let’s not forget that it was politicians who decided years ago to privatise local authorities’ building control inspections. Removing this as a public service had the unintended consequence of changing the relationships between the various parts in the ongoing building, repair and refurbishment process.

Calling for change

Dame Hackitt came to her task, unavoidably and naturally, with prior knowledge and subjective views and feelings about what she is examining. We might keep this in mind when considering her controversial and confusing recommendations about not banning flammable materials and instead advocating culture change. She claimed “restricting or prohibiting certain practices will not address the root causes”, adding “… a complete culture change would have the same effect as a ban anyway because companies would then no longer themselves choose to use combustible cladding”.

We may have personal doubts about that recommendation and wonder what led her to that conclusion (I confess I have not read her full report). And I wonder what led her to suppose that a ban would be circumvented, as she claims. Calling for culture change too, however pertinent, is easy to propose and hard to bring about. Many of the fish don’t want it and will frustrate it. Systems have ways of finding their own equilibrium and resisting disturbance, much to the frustration of those seeking radical change.

We know that improvement systems can themselves fail as much as the systems they are trying to improve may fail. Just think of the history of Hillsborough inquiries since 1989. It took several attempts to discover the truth and correctly assess whose views to believe. Will Moore-Bick’s and Dame Hackitt’s reviews get it completely right first time? Hackitt is finding it hard to convince a sceptical public that not recommending a complete ban on combustible cladding is the right action, especially when saying she would support a government ban. She may also be placing too much belief in the possibility of culture change.

Yet culture change is beginning to happen. Moore-Bick’s two-week long pre-enquiry stage of openly airing the experiences, feelings, and grievances of the tower’s surviving victims and relatives is both a humane and cathartic process, as well as politically shrewd. Otherwise it would happen anyway in a shadow system. (See How to intervene in the shadow system in the Resources Centre) Unlike the BA general manager, Moore-Bick was taking an enlightened view of his role, relationship and involvement in permitted dialogue.

The inquiry chairman’s unusual pre-inquiry step is now being spoken of a culture change in its own right. At the moment this novelty in the change process is limited to the improvement system, but it may portend a long-term change in the way the operational system works. It may signal a change in how residents are listened to and allowed to become involved in building critiques and refurbishments.

Thinking across contexts

Complex systems are messy. One reason for this is that the multiple contexts exist in silos with their own leadership teams and management processes that deliver results exclusively for those contexts. The management systems are not conceived and designed to manage the spaces between those contexts.

This transcontextual world that Nora Bateson writes about calls for liminal management and leadership of the spaces. An anthropological term, liminal here draws on ‘standing at the threshold between their previous way of structuring identity, time or community …’. The term is popularly associated with the familiar lack of joined-up thinking between silos. (See How to avoid and dismantle silos in the Resources Centre.) Without a major change of focus, management is trapped in traditional thinking within each context, pursuing its own interest while neglecting that of the whole. The spaces between these contexts lack the management and accountability processes that are needed to serve the whole system and all its stakeholders.

Looking at a larger scale, including the whole planet, and you may conclude that most of the world’s biggest problems (e.g. polluting oceans with plastic) are transcontextual. Here Bateson doesn’t call for stronger leadership. Indeed, an excess of strong leadership within the individual contexts makes the whole thing worse. As she points out, less leadership – if the siloed contexts is the only present outlet for people’s leadership energy in their jobs and organisations – might make the whole work better. We need to rethink what we want from leadership. Better, but at what, and for what?

So, given this problem of things failing in the spaces between contexts, what and where is the action that is needed to refocus leadership? The answer is always ‘at the next level above’ (whether organisational or individual). Fundamental transformation in thinking and in action will not come about if it is left to existing management structures in their respective silos. The same is true for leadership transformation even within those silos and within individuals.

A common mistake made by chief executives is to subcontract to individual managers and to training and development departments to bring about a shift in leadership and in its focus. (See How to clarify parties’ roles in leadership development in the Resources Centre.) But change will only come about when leaders and managers, however senior, are required, by a robust process, to account upwards and outwards for how they see their role and their stakeholders and how they collaborate. (See How to hold managers to account for their leadership in the Resources Centre.)This accountability requirement can come only from above. In some cases that is government. It is certainly a governance issue. (See How to conduct governance systemically in the Resources Centre.)

Studying leadership as a system

This is an example of what we mean when we say leadership itself can be seen, studied and managed as a system – the aim behind my book The Search for Leadership. At the level of the individual, the Institute’s website argues that every manager’s job consists of two roles. (This is where the separate improvement system clicks in. Remember Dame Judith Hackitt’s two systems: broadly, the industry’s present operating system, and her improvement-recommendation system).

The manager’s first role is doing the job as described, expected, appraised and rewarded. The second is questioning that job. Ask yourself “Why am I continuing to do what I am continuing to do the way I am continuing to do it?”. And ask your managers that too. In other words, making tomorrow work better than today.

It is this improvement aspect that is every manager’s leadership role. Repeating and maintaining the present is simply managing. Bringing about change is the true purpose of leadership, and it needs recognising and managing distinctively as part of the manager’s performance. (See How to get managers to show more leadership in the Resources Centre)

One criterion of success for Dame Hackitt’s call for change would be not only to understand the system failures, but to ensure that the roles, mindset, communication and integrity combine to prevent such things happening again.

Lessons learned from major inquiries are applicable at all system levels, including individual managers and leaders. Not recognising this learning perpetuates the status quo.