image credit The Times

The Munro Review of Child Protection

How the Institute’s model of systemic leadership helps embed the Munro approach.

(Note that this is now several years old, but the personal historic record shown here may have some value for professionals working in this field, especially since child tragedies keep recurring and the scope for improvement remains ever present.)

1. Background

On 10 June 2010, Michael Gove MP, at the time Secretary of State for Education, commissioned Eileen Munro, Professor of Social Policy at the London School of Economics & Political Science, to lead a review aimed at improving child protection in England and Wales. By the time the Review concluded its work in April 2011, it had published three reports: two interim reports with a narrow focus, and a final report published on 10 May 2011. These reports are in the public domain and were considered by the government.

Bill Tate has worked with Professor Munro, and has had prior involvement with children services, as well as once being an elected member of a London borough. Some of his ideas, methods and materials have been used by the National College for Leadership of Schools and Children’s Services in its peer support programme for Directors of Children Services.

His advice to the Review concerned leadership issues from a systemic standpoint. It had become apparent at the outset of the Review that Professor Munro’s conclusions and recommendations would be based on a systems-based perspective and approach to the organisation and practice in social work. The first of the Munro reports was devoted to analysing, examining and explaining this systems focus.

This website contains advice and material for use by:

- directors of children services

- other senior managers working in local authorities

- local authority chief executives (to whom a DCS reports)

- OD and HR professionals in local authorities

- elected councillors with lead responsibility for children services

- council leaders and other elected members with seats in cabinet and scrutiny committees

- agencies working in partnership with local authorities

- members of safeguarding children committees

- inspection services

- providers of training and development support to managers

- colleges, institutes, member bodies, and centres of excellence in this field

2. Advice submitted to the Munro Review of Child Protection

During the near year-long period of the Munro Review, Bill kept in close touch with Professor Eileen Munro, the review process and the interim reports. He took part in Department for Education discussions. On four occasions he has chosen to, or has been invited to, submit his advice on particular aspects.

3. What Baby Peter Connelly teaches us about leadership

In his tragically short life Baby P (Peter Connelly) learnt how cruel a place the world can be. But he taught us a great deal about systemic failure and leadership, and how it was denied him. Here we recount his story and offer the key lessons and messages about the new discipline of systemic leadership.

The extracts below are taken from the book The Search for Leadership: An Organisational Perspective (Author William Tate, published by Triarchy Press on 21 May 2009).

The earlier case of Victoria Climbié

‘Another high-profile case occurred in local government: the murder of eight years-old Victoria Climbié in the London Borough of Haringey in 2000. In June 2005 Lisa Arthurworrey, the disgraced social worker at the heart of the series of mistakes that failed to prevent Climbié’s murder, launched a legal attempt to win back her good name. She argued that she had been made a scapegoat to protect senior officers in Haringey Council. Her appeal was successful. Reported systems deficiencies in Haringey included the following:-

- an unreasonably high caseload

- lengthy investigation of cases lasting months and even years

- a culture that was hostile to cooperating with the police (there was a sign pinned on the wall ‘No Police’)

- flawed local procedures at odds with national guidance

- an absence of supervision

- a lack of people for social workers to share case worries with

- an unclear structure of accountability.

Baby Peter

Just two years later, in 2007, something similar happened again in the London Borough of Haringey, only a few streets away from Climbié’s murder. This time Baby Peter was killed by his mother Tracey Connelly and her accomplices Jason Owen and Steven Barker. His injuries included a broken back, gashes to his head, a fractured shinbone, a ripped ear, blackened fingers and toes, a missing fingernail, skin torn from his nose and mouth, cuts on his neck and a tooth knocked out.

Instinctively, we look for an individual in authority to blame: if not a social worker, then the pediatrician who examined Baby Peter and failed to notice the child’s back had been broken. In a tragic case like this, we assume that it’s a matter of someone’s professional incompetence, carelessness or neglect. There may well be an element of that, but systemic issues always begin to surface after a few days, such as professional agencies who didn’t share information. Even the pediatrician is able to describe her environment as problematic: she was not handed appropriate background file notes.

In this tragic case, systemic failures that were reported included:

- insufficient strategic leadership and management across the board

- failure to comply with recommendations about written records

- failure by the local safeguarding children board to question the agencies that reported to it

- lack of independence in its approach

- lack of communication and collaboration between agencies

- failure to identify and address the needs of children at immediate risk of harm

- inconsistent quality of frontline practice among all those involved in child protection.

How the service operates

Looking at how the service operates we find ‘the government has now centralised the system and, crucially, split it between a front-end referral and assessment function that filters incoming cases, and a back end that handles demand for ongoing care’. Baby Peter was seen on 60 occasions by Haringey officials, the police and hospitals, yet very few professionals saw him more than once. The new working system replaced the local teams that had had responsibility for handling cases from start to finish. At its heart is the Integrated Children’s System (ICS), a computerised recording, performance management and data-sharing system, which relentlessly chivvies officials to complete their on-screen documents.

The effect of the computer system

Workers report being more worried about missed deadlines than missed visits … The computer system regularly takes up 80% of their day. … use of tick boxes was criticised because of a lack of precision that could lead to inaccuracy. … If you go into a social work office today there is no chatter, it is just people tapping at computers.

Work by Sue White from Lancaster University highlights the role of the ICS in her explanation:

‘ICS’s onerous workflows and forms compound difficulties in meeting government-imposed timescales and targets. Social workers are acutely concerned with performance targets, such as moving the cases flashing in red on their screens into the next phase of the workflow within the timescale. … social workers report spending between 60% and 80% of their time at the computer screen.’

Discontinuity

John Seddon of Vanguard Consulting explains why children get seen by lots of different people. Every time a child is referred, it is treated by the IT system as a ‘new’ case. Those who visit will be predisposed to avoid taking the child on. Why? If you take a child on, the computer system will allocate ‘workflow’ activity targets, hard-wired to a status that gets managers hovering if anything is ‘going red’. It is better to discount relatives’ or neighbours’ reports and/or find any reason not to take the child on.

Some systemic questions about leadership arise:

- Who has clear responsibility for social workers’ environment (for what surrounds them, separately from their competence and daily performance; i.e. for the fishtank rather than the fish)?

- Who has responsibility for the design, functioning, monitoring and improvement of the system within which social workers are required to perform their jobs, and for how this responsibility is divided between the local authority and the government’s Department for Children, Schools and Families?

- How is the accountability for these aspects of officials’ performance managed in the ordinary course of events; i.e. before things go wrong (including the roles of elected councillors, since they were deemed to have failed too and were removed)?

- When serious cases are reviewed (as they are regularly), how do they guard against unconsciously noticing only evidence that supports their earlier decision? Do they, for example, use a Devil’s Advocate? Do they use different chairpersons to avoid defensive behaviour?

The danger is that, in place of clear answers to such tough questions, the public will yet again be offered the balm of ‘lessons will be learned’.

Playing politics

Almost as shocking as Baby Peter’s death is the naivety shown by Ed Balls, the UK government’s Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, who insists that ‘there is nothing wrong with the system and Haringey was a special case’. Has he not read Ofsted’s report? Instead Balls has ordered council children’s services chiefs to undergo intensive training programmes. Without wishing to discount training, it should be recognised that it has less leverage in situations like this than other systemic interventions.

He went on: ‘We must do more to value good leadership across the whole of children’s services’. He makes the common mistake of equating training with improved leadership. If ever evidence was needed of the importance of understanding and taking a systemic leadership perspective and the uphill battle of awakening influential figures to it, the minister’s woeful response provides it.

Sharon Shoesmith

Sharon Shoesmith, the dismissed Director of Children and Young Persons Services in the London Borough of Haringey, was criticised for providing insufficient strategic oversight to her department. As with Lisa Arthurworrey in the Climbié case, Shoesmith became a scapegoat, conveniently protecting the minister Ed Balls, Ofsted and others who had a share in the responsibility for the design and running of the failed [national] child protection system.

Senior executives’ role options

This raises the question of how clearly Shoesmith saw her role and involvement in Systems 1, 2 and 3. [NB: This structure of three ‘role systems’ which every senior executive has available to call upon is explained fully in the book on pages 215-218.] How did she allocate her time – between delivering today under the present system (‘System 1’) and improving the system to secure tomorrow (‘System 2’), and between a hands-on role leading change (‘System 2’) and an overseeing one where others seek and propose solutions and make the change (‘System 3’)?

For senior executives there is a risk of becoming reactive to the needs and demands of others … of confusing the three role systems, of ending up responding to the urgent and tactical short term ahead of the important and strategic longer term, and of addressing the people rather than the system. This is a difficult enough balancing act if undertaken consciously. It is almost impossible without the help of a mental model like that above, a coach to prompt reflection, and a superior to ensure accountability.

Shoesmith’s supervision

This raises another important question in the Baby Peter case: what role in this scenario was being played by the person to whom Shoesmith had to account for her performance? Was it clear to her? Was it clear to them?

In seeking improvement the starting point is to change senior executives’ perceptions of their various roles and involvement in these three systems. Such a discussion should be part of a performance review.

Risks if there is no System 2 or System 3

Without a mental model of the kind described above, there is a risk that incidents will be ‘solved’ by finding someone to blame, an explanation (‘staff member sick’), by someone being asked to make a procedural fix, and then by offering customers, the public and media a reassurance that ‘lessons have been learnt’. What is usually missing is a process of developing and culturally embedding the permanent systemic leadership capability that the organisation needs.

Accountability for child protection

An increasingly common problem for organisations is that the everyday operational system crosses many boundaries. In the case of child protection services, there are several major parties who collectively deliver that system. These include the local authority, police, schools and hospitals. Added to this list are several other bodies and agencies: the government’s Department for Children, Schools and Families, Ofsted, the Healthcare Commission and the Audit Commission. There is also the cross-party Commons Select Committee for Children, Schools and Families, which can summon officials to appear before it and ask them to account for their action, yet which has no formal authority to hold them accountable.

In Baby Peter’s case, Haringey Council’s Director of Children and Young Persons Services seemed to be expected to hold the ring and shoulder the blame for the system’s failings. But she didn’t design the overall system, or the national IT system that supports it.

In complex systems like this the government needs to be more clear about where accountably lies and how a fair accountability process should operate.

Single-point or multiple accountability

Popular advice seems to be to make an individual alone clearly responsible for an activity. Conventional wisdom says this assists that person’s motivation. It is also claimed to be easier to hold them to account when things go wrong; if several people are collectively involved it is more difficult to pinpoint where responsibility for failure rests. … but the advice in favour of having a single person who is responsible and who alone can be held to account may simply not accord with the modern-day realities of complex organisations. As we saw with the Baby Peter case, this is particularly so where partnership working is built into the structure, where responsibilities may need to be held jointly. In such instances, a system for holding numbers of managers jointly to account would be appropriate and should be used, but this is rarely practised.

A duty to cooperate

In connection with the Victoria Climbié case the Audit Commission report identified that Children’s Trusts were failing to ensure that the various parties were fulfilling their duty to cooperate. So what did the Government do? It announced that it would hold each of the parties individually to account. At first glance this sounds fine, but it is actually the opposite of what the government should be doing. Individual accountability reinforces each party’s perception from their own silo’s perspective and encourages them to point the finger elsewhere. If you want the parties to see themselves as a joint service and to be managed as a team, they need to be held to account collectively. In practical terms that means two things:

First, they must be brought together and collectively charged with proposing upwards (to government – effectively the Secretary of State for Health) for how they will themselves collectively manage their duty to cooperate. Secondly, they must be brought together to account to government for how they have cooperated collectively.

A question of competence – but whose?

Was the failure in Haringey’s child protection service caused by individuals’ incompetence? The book critically examines the contribution made by competency frameworks to any corporation’s leadership development and improvement. After major failure, the gut response of most people including the media and government ministers is to find out whose performance showed a lack of competence. The Ofsted inspector’s focus ‘is on corporate and collective competence and delivered system performance, because that is what the public ultimately requires from child protection services’. A particular social worker’s (or even departmental director’s competence – whether assessed as a capability or as actually performed) is a subset of that, although it is what most people, including the media and government ministers, choose to concentrate on in cases like this.

Measure for Measure

The case provides a graphic reminder of how measures of competence (both individual and collective) in a Council’s Department of Children and Young Persons Services serve as a simple and simplistic proxy for the complexity of real performance. There are several reasons why these measures can never constitute actual performance:

- The measures comprise a limited range of metrics deemed by certain planners to be sufficiently indicative of overall performance.

- The metrics are chosen because they are measurable (e.g. completion of records), while important but immeasurable ones are omitted (e.g. quality of relationships).

- The measures represent just one party’s contribution (i.e. the Council’s) in a complex web of interactions within a wider system that includes police, schools and hospitals.

- The measures require an inspection, which is a subjective process that calls for interpretation.

- The managers who are the target of the inspection selectively provide the data to an Ofsted inspector.

Where were the hidden incentives in the system?

Ofsted’s routine inspection of Haringey’s Children and Young Persons Services beginning in November 2006 and published in November 2007 (shortly after Baby Peter’s death in August) had ticked all the right boxes and awarded the department ‘3 Star’ status of ‘Good’.

Yet a year later when Ofsted, the Healthcare Commission and Police conducted an enquiry into the department, it found gross systemic failure, at which point Ed Balls, the government’s Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, removed Haringey’s director from her post. How could Ofsted effectively overturn its judgement? An inquiry into the inquiry showed that Ofsted had originally allowed itself to be hoodwinked. The assessment method was open to manipulation. ‘Officials in the Council were able to “hide behind” false data to earn themselves a good rating’. The motives are clear: successfully jumping through the government’s hoops brings resources, money and political advantage.

It’s the wrong question

The problem lies with the inspector’s question. That question forms a crucial part of managers’ environment. Inspectors are interested in the question: ‘Is the service up to standard?’. A high rating lets everyone relax, and a low one damns them. This is the wrong question to be asking. They should be asking: ‘What are you doing to improve?’. A culture of learning and continual improvement would then replace a culture of cheating. Volition in an improvement mindset is very different from that engendered by a compliance one.

Keeping leadership in mind

When taking up their job, most managers who see themselves as having a clear leadership role gradually lose sight of their high hopes and aspirations for change and improvement. They fall victim to the pressures that come upon them. They find themselves reacting to demands, requests and circumstances. The managers become bureaucratised; their jobs are eroded by entropy. They forget why they were put there.

The challenge to overcome this trap is mental. All managers should produce and then keep alive in their mind a plan for how to structure, prioritise and use time and resources for that part of the job that concerns their leadership role. They need to write answers to these questions on a piece of paper, keep it to hand, remind themselves, and reflect frequently on them:

- What am I trying to achieve with my leadership?

- What do I need to change around here?

- Who are my customers and what leadership do they need from me?

- What are my leadership priorities?

- How will I manage the time I need to allocate to my leadership role?

- How will I enable others to use their leadership?

- What is the system doing to me and what am I doing to the system?

- How will I successfully account for my leadership?

[Update: Following strong criticism of the Government-imposed Integrated Computer System (ICS), on 22 June 2009 the Government announced that it was rescinding the requirement for local authorities to use the ICS or lose funding. With immediate effect they would be free to use local discretion within a simplified national framework.]

4. Blog on Child Protection

Bill launched his blog (www.systemic-leadership.blogspot.com) on 27 October 2009. A recurring theme has been child protection. A series of six posts appeared in April/May 2010 on the subject of Baby Peter Connelly, the role of the inspector Ofsted and the minister Ed Balls, and the court hearing the case of the dismissed Haringey director of children services Sharon Shoesmith.

5. ‘Sometimes it’s the workplace that’s stupid, not the staff’, (Response column of the Guardian, 11 November 2009)

“Child abuse inquiries should accept that social workers are often failed by the system”.

William Tate

Eileen Munro argues that we should replace the highly personal investigations into child protection failure (like that of Baby P) with a more systems-based approach, similar to that used after an air crash (‘Beyond the blame culture’, 04.11.09). For a plane disaster, she says, an investigation is “most unlikely to consider that the pilot may have caused the crash through laziness or stupidity”. By contrast, “investigations triggered when a child is killed or seriously injured in a domestic setting … make no such assumptions about the professionals involved”.

My airline background and public-sector work supports her case. In these two different contexts the expectations, prejudgment and treatment are quite different. Social workers are, as Munro says, more likely to be assumed to be “stupid, malicious, lazy or incompetent”. In child protection work there is a complex and unpredictable human system of interpersonal relationships. Like flying, there are procedures to follow, of course; but each family situation is unique, bringing a need for discretionary judgment and a tailored response. This makes investigations less amenable to box-ticking and more prone to arbitrary ratings. The process fuels scapegoating and tough, simplistic, action by politicians.

In a serious social-work case review, the question is repeatedly asked: “Why don’t staff follow procedures?” But the workplace itself can be stupid, not the workers. Is it wise, for example, to have a rule about the length of a family visit? Munro wisely prefers to ask a system-based question: “What hampers staff from following procedures?” But the system is more than an obstacle: it is the actor. “Why is the system producing this result?” is a bigger and better question.

Munro points out that the system includes “the full range of people, procedures, skills, tools, organisation and culture”. A full systems perspective is also concerned with the following questions: who is allowed to talk to whom; how is accountability managed; how does leadership work; how does the organisation learn; how does the hierarchy operate, and how is power used?

In the fishtank analogy of a workplace, it is the quality of the water in the fishtank that determines the lustre of the fish. It is what people are surrounded by that shapes their work behaviour. Yet most onlookers see only the fish, and then blame them.

Munro asks: “How can we build a system that is more likely to get it right?” The answer is not to roll out the systems approach only when we need to find out what has gone wrong; it is to embed this understanding of how organisations work (and fail) into every senior manager’s job. Every system falls short and needs leadership to improve it.

Remember the case of Lisa Arthurworrey – the “disgraced” social worker involved in Victoria Climbié’s death. Years later, she went to court to regain her professional reputation: the court decided that the system in Haringey had failed her and not the other way round.

6. A facilitation approach for improving leadership

The question of leadership always arises when a major programme is going to fundamentally change the way the organisation works. Deep systemic change has an impact on leadership, and change makes new demands of leadership. The process of leadership inevitably will, but also must, change.

Two things in particular stand out. First, the leadership that is required has to take account of how organisations are, and interact as, systems. Secondly, lots of leadership is needed, coming from all levels, not just a few top managers. This calls for a clear and new leadership agenda, one that addresses the required leadership strategy, learning and support needed to embed new ways of working, especially ways that see the organisation as a system. Systemic leadership is a process for understanding, expanding, releasing, promoting, improving and applying the organisation’s leadership capability. The approach blends the understanding of how an organisation works that comes from systems thinking, with leadership interventions that draw on organisation development.

This is an applied method. It works on practical leadership issues that affect managers as they try to exercise new ways of leading. The practical issues concern what managers are trying to achieve, what gets in the way, and what is needed from the system to free up and make use of available leadership energy. This approach is different from teaching individuals leadership theory in a classroom and hoping that they will find useful things to apply their learning to. We are more concerned with what is happening outside the classroom than inside it. Classroom time is used mainly for practical workshops, with easy access to relevant systems leadership theory as required. The key point for the organisation is that the learning has to escape from the classroom and from individuals’ heads and be applied and used to challenge, change and deliver.

The aim is to target benefit on the whole organisation. What matters is that the organisation should be well led as a whole. Having good individual leaders is not sufficient. Many managers will already be excellent leaders anyway. We do not formally attempt to teach leadership to managers. We work with the system wherever leadership is and where it needs to be, and wherever issues and opportunities arise, so that the system manifests leadership that is continually improving. The learning dynamic is live and experiential, not formal, predictable and controlled, mirroring the work environment in which leadership is increasingly situated.

This means working at the point where people and the organisation’s daily practicalities come together. Sometimes the work and the learning is planned, as in workshops and in coaching, mentoring and guiding sessions, and sometimes more spontaneous with support to hand, including by phone and email. These practicalities include all those things that go on around and between people as they try to go about exercising personal leadership in a dynamic and political environment. Think of this like a fishtank. The leader needs to be able to see and give attention to what people, including managers, are expected to swim in as well as what they are personally good at doing. How healthy is the ‘fishtank’? Who ensures that it’s clean? Where does nourishment come from? And what about toxins? The ‘system’ that surrounds people is very powerful and explains much about how well they perform, either providing opportunities or blocking them. This system – including leadership-related policies, practices, procedures and structures – may itself need redesign; for example, performance management systems and how managers are held accountable specifically for their leadership. Leadership is a frequent victim of waste, and this too needs to be discovered and stopped.

Our approach to leadership is not an intervention or an event or simply a series of workshops. It is a more like a way of living leadership. It means leading an organisation in a way that deeply affects and infects the culture. It becomes ‘the way we do leadership round here’. It is concerned with more than implementing a change programme by some planned end date. It’s more like a virus, changing the way managers see their role as leaders, how they make their choices, and how the system responds.

7. Where a systems perspective can help

A systems way of thinking may be applied to each of the fields set out below. Acted upon together, they will help to deliver a whole systems approach.

1. How improvement works

Whole system

Design, conduct and evaluate the overall intervention to improve childcare in the local authority area.

Component parts

Design, conduct and evaluation of component parts of the intervention in the context of the whole, for example:

- Strategies for improvement

- Organisational learning

- Training, development; e.g. any managers’ action learning programme

- Monitoring and managing anticipated risks to the change programme; e.g. slipping back into old habits when under pressure or criticism

- Monitoring and reducing the natural growth of bureaucracy

- Monitoring and reducing the many forms of waste, including leadership waste

- Increasing the range and ease of discussibility

- How recommendations are acted upon, arising from:

– Munro report and evaluations

– Serious case reviews

– Ofsted inspections

– Government directives/initiatives

– Front-line workers’ daily experience

– Reflective practice/active reflexivity

– Project Board

– Systems Change Board

– Cabinet reports, etc

-

2. How the providers work (both intended and actual)

- Allocation of resources

- Reporting structure

- Laid-down processes

- Use of hierarchy

- Distribution of power

- Role and composition of multi-disciplinary Social Work Unit

- Role of clinicians

- Role of Group Managers

- Role of the Unit Coordinator

- Role of Children’s Practitioner

- Role of Project Board

- Role of other support units and services

- Role of Joint Resource Allocation Panel

- Role of the Weekly Resource Panel

- Skills and professional disciplines

- Quality of inter and intra relationships

- Who takes decisions and matrix of responsibility

- Acts of omission as well as of commission/decisions

- Keeping records

- Performance management (of individuals, teams and the system)

- Being held accountable (processes and summoning)

- Discipline

- Training

- Attendance, sickness

- Time management

- Risk aversion and risk management

- Methodological approach

- Serious case reviews

- Networking

- Commissioning

Agency and service partners, including police, GPs, courts, etc.

Who takes the lead, contact, liaison, communication, relationship, reporting, collective performance, and the equivalent of the above items as appropriate.

Environment and other stakeholders, including:

Government Department for Children, Schools and Families, Ofsted, NSPCC, foster carers, etc.

3. How the work works (both intended and actual)

- How work comes in (contacts, enquiries and requests)

- Work flows

- Work analyses

- End-to-end times

- Timescales

- Caseloads

- Prioritising

- Complaints

- Assessments

- Decisions

- Customer pull

- Bottlenecks

- Feedback

- etc.

4. Those who need child protection, care and support

Children, young people and their families:

- New Cases

- Looked after children

Needing:

- family support

- to be taken into care

- adoption

- fostering

- physical and emotional development

Concerning:

-

- abuse

- behavioural difficulties

- schooling

- alcohol

8. The Munro Review Reports: comments and extracts

Context

The context for comments are the following reports by Professor Eileen Munro and her colleagues:

- The Munro Review of Child Protection – Final Report: A child-centred system (2011)

- The Munro Review of Child Protection – Part One: A systems analysis (2010)

- SCIE Children’s and Families’ Services Report 19: Learning together to safeguard children: developing a multi-agency systems approach for case reviews (2008)

Key extracts from these reports are reproduced in Extracts from… further down this page.

Comments

The government’s terms of reference for the Review do not expressly ask Professor Eileen Munro and her team to include matters of leadership in their deliberations. And she admits that this area falls outside her field of expertise. So direct references to ‘leadership’ in the reports are fairly limited. While that comes as no surprise, more specific advice on this aspect may have been helpful to child protection managers, as well as to government ministers, Whitehall civil servants, and regulatory inspectors.

A factor in the limited amount of direct advice on leadership may be that politicians and others outside the field of management and leadership studies may assume that, provided the changed policy and business brief are clear, then professional managers should and can be trusted to draw on their own leadership experience and ability. That would be a mistake, in our view. Politicians are inclined to believe that any further need can and will be met through training, and they sometimes unhelpfully mandate this – in spite of evidence that leadership training is a relatively weak lever to pull on when it comes to shifting culture, distributing power, and bringing about systemic change.

That said, the Munro Review’s direct advice on leadership is a mere fraction of what the reports actually contribute to the leadership discussion. Leadership is more than style, behaviour, competence and role; it is also about perspectives and challenges. And these elements of leadership arise from the changing work context. On these aspects alone the reports make a major contribution to improving leadership in child protection, especially in respect of adopting a systems perspective.

Predictably, the final report and accompanying publicity states that ‘strong leadership’ will be required, including from government (which is usually taken to mean central rather than local government). This ‘strong’ terminology goes down well with media, the public and managers, though what is meant by ‘strength’ is rarely defined. There is a risk in this terminology. Such advice and assumptions should carry a health warning, as other serious writers on leadership have pointed out. Strong government may seem to be at odds with Professor Munro’s advocacy of giving local authorities greater responsibility and freedom from central government. In that instance, ‘strength’ includes the political courage to question one’s own role, back away, delegate and trust, permit variety, and not try to micro-manage nationally someone-else’s local business.

If the essential ‘what’ of child protection service provision remains centralised (in terms of laying down key principles), the ‘how’ should be left to local judgement. This broad ‘rule’ about distinguishing between the what and the how extends down the management chain to professional front-line staff. It is also telling that evidence to the Review reveals that most bureaucracy is locally generated.

There are examples of pressurised poorly-rated local authorities relying on ‘strong’ leadership as the means of getting to grips with a failing child protection service. Strength is sometimes expressed as firmer plans, tougher edicts, stronger controls, and getting people to add their signature to agreements. Such means-to-an-end may count highly with inspectors. But, as Professor Munro points out, the need is to shift the focus from judging success based on monitoring adherence to management processes to the resulting outcomes on children, young persons and families. In all the above respects, leadership qualities of awareness, sensitivity, courage and determination will be needed. But more than the leader, it is the system that needs strength.

Studies in complexity science show that undue faith is put in plans, where claimed predictability is a hostage to fortune. Control too is an illusion. The problem (and paradoxically, another personal challenge facing leaders) is well captured in Tony Blair’s repeated question to ministers: ‘I understand the policy; now what are the politics?’. Practically, ‘to make the policy fly’ (as Blair puts it), the politics are a necessary reality. But this carries the risk of pushing behaviour in the wrong direction. Political considerations include the fact that politicians (local and national), inspectors, media and the public are falsely reassured by seeing managers’ plans and the appearance of control, so favoured by command-and-control hierarchies.

Such political realities echo the way that the Labour Government initially convinced the public that merely announcing targets was tantamount to assuring improved levels of performance. If managers have subsequently lost some faith in targets (at least those of others if not their own) many still believe that detailed plans bring both delivery and reassurance. Even if managers acknowledge the limits of improving performance via planning and controlling, and even if they recognise that ultimately each individual makes their own meaning of situations and mandates, they may still feel a political/PR need to imply otherwise. But they also risk coming to believe their own rhetoric and mis-spending their effort on what is rational and tangible, on what Professor Munro calls technocratic approaches rather than socio-technical ones.

Munro’s call for those in senior leadership positions to be more closely in touch with their organisations is important. A command and control approach can easily lead to physical, knowledge and strategy separation from the front line. Complexity experts also point out that management’s reputation depends on sleight of hand concerning somewhat illusory powers. Humility and approachability too are therefore part of the leadership challenge.

For detailed and practical advice on a myriad of leadership issues, dilemmas and points like these, and how best to use appropriate leadership, readers can draw on the Institute’s services and rich bank of resources.

1. Extracts from the Munro Review of Child Protection – Final Report: A Child-Centred System

Key passages have been highlighted here in red.

7.4 Reform of the child protection system will depend heavily on strong, skilled leadership at a local level. Leaders need to know their organisations well and constantly identify what needs to be realigned in order to improve performance and manage change. Developing these leaders is, therefore, critical to success. The review is aware of the Government’s support of the sector to develop a strong cadre of skilled leaders and it is essential that this continues if the child protection system is going to be well managed – particularly through a period of change. The work that has been done by the National College of Leadership provides a valuable resource.

7.5 Any change to local child protection systems will need the full support of the whole organisation so that the required actions are properly supported and facilitated. The review has found, for example, that most bureaucracy which limits practitioners’ capacity and ability to practise effectively, is generated and maintained at a local level. This includes financial and personnel arrangements, procedural requirements, poorly functioning or under resourced ICT arrangements. To undo these arrangements requires commitment, resource and focus. To generate and complete change of this scale also requires different behaviours and expectations from local politicians, chief executives and senior officers, so that the demands placed on child and family social work services are directly related, so far as is possible, to improving and supporting frontline practice. A one-size-fits-all approach across a local authority’s departments is unlikely to address the current complexities and vulnerabilities of child and family social work or sufficiently support the necessary changes ahead.

7.6 Managers have to satisfy the needs of both today and tomorrow. They provide day-to-day stable and consistent management of child protection services. But they also exercise leadership to challenge and bring about change and improvement focused on securing a better future. Leadership will be needed throughout organisations to implement the review’s recommendations successfully, especially to help move from a command-and-control culture encouraging compliance to a learning and adapting culture. Managers also need to balance improving service efficiency and effectiveness with the need to manage increasing financial pressures.

7.7 Leadership is often only understood in terms of individuals at the top of the hierarchy, but it is much more than the simple authority of one or two key figureheads. Leadership behaviours should be valued and encouraged at all levels of organisations. At the front line, personal qualities of leadership are needed to work with children and families when practising in a more professional, less rule-bound, way. Practitioners need to challenge poor parenting, and have the confidence to use their expertise in making principled judgments about how best to help the child and family.

7.8 Changing the way organisations manage frontline staff will have an impact on how they interact with children and families. There is evidence that workers tend to treat the service user in the same way as they themselves are treated by their managers.

7.9 For some organisations, the change will need a move away from a blaming, defensive culture to one that recognises the uncertainty inherent in the work and that professional judgment, however expert, cannot guarantee positive outcomes for children and families. The organisational risk principles listed in chapter three need to underpin practice. In child protection, a key responsibility of leaders is to manage the anxiety that the work generates. Some degree of anxiety is inevitable.

Whilst practitioners have a key role in protecting children, their safety and welfare cannot be guaranteed. Additional anxiety is fuelled by the level of public criticism that may be directed at child protection professionals if they are involved in a case with a tragic outcome. In the review’s analysis of why previous reforms have not had their intended success, unmanaged anxiety about being blamed was identified as a significant factor in encouraging a process-driven compliance culture. As William Tate wrote to the review:

‘Managers should use their leadership role to monitor and improve (i) the way the system continually learns and adapts; (ii) what the system requires of frontline workers; and (iii) how healthy and free of toxicity is the work environment. They will need a high level of awareness of how organisations perform as systems’165

164 Schneider, B. (1973), ‘The perception of organizational climate: The customer’s view’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 1973, 57, pp248–256.

165 Submission to the review by William Tate, Fellow of the Centre for Leadership Innovation at the University of Bedfordshire, and the Director of the Institute for Systemic Leadership.

The full report can be downloaded at http://www.education.gov.uk/munroreview/

2. Extracts from the Munro Review of Child Protection

Part One: A Systems Analysis

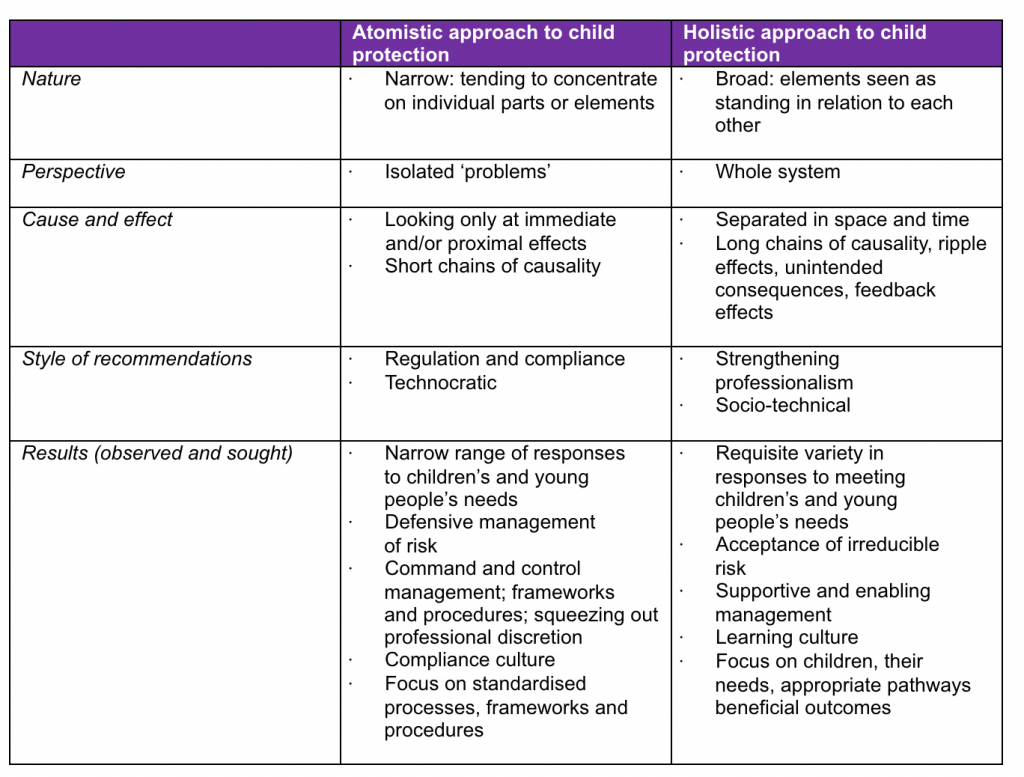

Atomistic and Holistic Approaches to Child Protection

Doing, thinking and learning

1.15 In broad terms, the difference between single and double loop learning can be characterised as:

‘A concern with doing things right versus a concern for doing the right thing.’

1.16 In child protection terms, single loop learning is a way of characterising the compliance approach underlying some reforms. As an example, has the set form on this case been completed and has this been done within the set deadline? In contrast, double loop learning leaves space for professional judgment and the questioning of set targets if a given situation does not conform to the technocratic model. As an example, is completing the Initial Assessment Form within a ten-day period the right measure of our success in helping this particular child? If not, can we change the target to reflect a more accurate measure?

1.17 Atomistic approaches to learning are characterised by single loop learning. As with the thermostat, the question that is asked is: are we doing what is specified? With single loop learning, targets are set for the child protection system and its performance is monitored to check (=’learn’) whether the performance matches the targets. If not, then action is taken to change what is going on in the system and put things right; i.e. to hit the target.

The socio-technical approach

1.21 The fourth systems theory idea that the review will draw on is that of the ‘sociotechnical system’, contrasting the ‘technical’ approach to understanding child protection with a ‘socio-technical’ approach. A ‘technocratic’ approach assumes that a given analytical problem is clear, with consensus about aims and that implementation of recommendations will be via hierarchical chains of command. In contrast, a ‘socio-technical’ approach assumes the individuals involved and how they work together are just as important as any analytical problem. There is no presumption about consensus regarding the problem: aims might be hard to agree on, and implementing change may require support from a range of partners. This approach does not undermine the value of rigorous analytical thinking, but argues for a balance of abstract analysis and consideration of human relations. The nature of the child protection work has to mean that professional practice and policy makers are open to variety in both defining what help is being sought but also in any response to it. The most effective means of intervening in families is to try to provide the breadth of professional expertise that meets the breadth of their needs.

‘The technocratic view is faulty, not because it is incorrect, but because it is incomplete.’

1.25 Taking a socio-technical approach to child protection points to the work being essentially ‘social’ even though there is a place for technical aids; it deals with people not with objects. To paraphrase Chapman (2004), you can deliver a pizza but you cannot deliver a child protection service:

‘All public services require the ‘customer’ to be an active agent in the ‘production’ of the required outcomes. Education and health care initiatives simply fail if the intended recipients are unwilling or unable to engage in a constructive way; they are outcomes that are coproduced by citizens.’

Chapman, J. (2004) System Failure: Why Governments Must Learn to Think Differently, Demos

3. Extracts from SCIE Children’s and Families’ Services Report 19, Learning Together to Safeguard Children: Developing a Multi-Agency Approach for Case Reviews

The basics of the approach

The cornerstone of a systems approach is that individuals are not totally free to choose between good and problematic practice. Instead, the standard of performance is connected to features of people’s tasks, tools and operating environment. …The goal of a systems case review, then, is not only to understand why a particular case developed in the way it did, for better or for worse. Instead, the aim is to use one particular case as the means of building up an understanding about strengths and weaknesses of the system more broadly and how it might be improved in future.

1.1.1 A new ‘systems’ approach to learning

In brief, a systems approach seeks to provide a nuanced understanding of front-line practice by getting behind what professionals do and illuminating why they do what they do. In reviewing past practice, this involves taking account of the situation they were in, the tasks they were performing and the tools they were using etc, in order to highlight what factors in the system contributed to their actions making sense to them at the time. This allows an understanding of how both good and problematic practice are made more or less likely depending on factors in the work environment. Ideas can then be generated about ways of reshaping the environment or redesigning the task so that it is easier for people to do the task well and harder to do it badly.

1.2.1 Learning together vertically: policy makers and senior/strategic managers need to learn about and from the realities of front-line practice

On the one hand, it is right and proper for ministers to determine what the priorities and directions of government policy and action should be. On the other hand, however, it is increasingly difficult for them, or those responsible for strategic and operational management within individual delivery agencies and the interagency system (epitomised, in England, in Local Safeguarding Children’s Boards, or LSCBs), to dictate with any confidence how exactly to achieve those goals. Two key, overlapping issues are involved.

Firstly, the delivery of public services always depends on the actions of people and institutions that cannot be directly fully controlled by central government departments and agencies (Chapman, 2004). A so-called command and control approach is, therefore, of limited use. Secondly, children’s services is a ‘complex’ system that means that the relationship between cause and effect is not straightforward. Implementation plans are, therefore, easily scuppered by the non-linear dynamics both within and between delivery organisations. Put simply, policy and management interventions and guidance may have unpredictable and unintended consequences. Again, therefore, the challenge of translating policy aspirations into practice brings the issue of learning to the fore. Rather than presuming to know best about the ‘how’ of achieving policy goals, those in top positions in the hierarchy need opportunities and methods for learning from front-line workers and their managers. This is imperative if feedback is to be obtained about the actual effects of new policies and guidance, strategic and operational decisions on the ground. By calling this report ‘learning together’, then, we draw attention to the need not only for horizontal learning across agencies but also for methods of learning together vertically, between practitioners and front-line managers and those at a senior/strategic level locally as well as policy makers at a national level.

1.4.1 By ‘systems issues’ do we just mean policies, procedures and protocols?

When talking about ‘systems’, people often think in terms of policies, procedures and protocols, hence the question: ‘Are the appropriate systems in place?’. In the systems approach that we are presenting, the term ‘systems’ is used in a far broader sense and includes all possible variables that make up the workplace and influence the efforts of front-line workers in their engagement with families. Importantly, as well as the more tangible factors like procedures, tools and aids, working conditions, resources etc, a systems approach also includes more nebulous issues such as team and organisational ‘cultures’ and the covert messages that are communicated and acted on. It treats these apparently softer factors as systems issues as well.

Commonly, talk about systems as policies, protocols and procedures includes an assumption that protocols and procedures are a key part of the solution to whatever problem in front-line practice is at hand. Compliance with procedures is, thus, presumed to be linked to safety and the attainment of good outcomes. There are two problems with this. Firstly, at best, procedures only provide outline advice on what to do with the result that in many cases procedures can be followed but practice may still be faulty. Secondly, while procedures are generated from the wisdom of experienced workers and, increasingly, according to evidence-based knowledge, there is no empirical evidence to show that they are ‘right’ in the sense of guaranteeing the best outcomes for children. There is always a possibility that they may themselves contribute to adverse outcomes. Consequently, in a systems approach one assumes that the actual impact of procedures needs to be confirmed by findings. They are seen as part of the work environment to be reviewed, as they interact both with workers and other factors to influence the quality of front-line work.

1.4.6 Does ‘no blame’ mean no accountability? What about the ‘bad apples’?

Descriptions of a systems approach as a ‘no blame’ approach also often lead to concerns that there is no recognition of personal responsibility or accountability in the systems model. Hence the question arises: ‘What about the bad apples?’ …

Consequently, it has been argued that a better description of the objective is the development of ‘an open and fair culture’ which ‘requires a much more thoughtful and supportive response to error and harm when they do occur’.

What the systems approach highlights is that holding a particular individual or individuals fully responsible and accountable is often highly questionable because, as stated earlier, typically incidents arise from a chain of events and the interaction of a number of factors, many of which are beyond the control of the individual concerned. Decisions about culpability, therefore, need to be far more nuanced and tools have been developed to aid this process.

2.2.6 Defining a system, its sub-systems and boundaries

In place of a person-centred approach, then, the systems approach places individuals within the wider system(s) of which they are part. This raises important questions about how we define and identify a system. A system can be either natural (for example, the human body) or man-made (for example, a child welfare system). It is understood as consisting of a set of interacting elements – so the child welfare system is made up of multiple individual agencies and professions as well as the inter-agency system epitomised in LSCBs. The elements, however, include not only people but also technology – a socio-technical system. All are brought together for a particular purpose or purposes – to safeguard and promote the welfare of children.

Systems are seen to have boundaries (some people or elements are seen as inside, others are outside) but the boundaries are permeable – there is movement across them so the system is responsive to outside forces. Each person or element within the system may be a part of other systems as well. The total system, therefore, can be thought of as made up of sub-units or sub-systems. So teachers and others have a role in the multi-agency safeguarding/child protection system but also in the education system.

The picture becomes more complicated, however, because these sub-systems can also be regarded as themselves systems in their own right containing their own sub-systems. So the education system, a sub-system of the child welfare system, contains schools, which can be regarded as systems. Conversely, the child welfare system can itself also be regarded as a sub-system of a larger macro-system, if we see it, for example, as part of a government department and ultimately the welfare state. A system’s behaviour is understood as arising from the relationships and interactions across the parts and not from the individual parts in isolation. Where you draw the boundaries, therefore, and whether a particular element is considered a micro- or macro-system depends on where you are looking from. This makes the boundaries of any investigation somewhat ambiguous. While the range of potential parts makes it difficult for any one inquiry to study all sub-systems in depth, where you put the boundary of any investigation is based on a theoretical assumption and not an objective fact.

Leadership Advice given to the Munro Review

A systems-based leadership strategy for implementing change

10 October 2010

Improving accountability processes

22 February 2011

Questions when holding managers to account

15 March 2011

Leadership principles

18 April 2011

Blog posts

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.